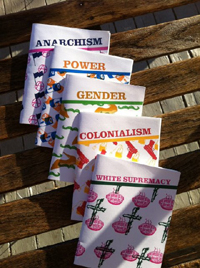

The Lexicon pamphlet series, a new project of the Institute for Anarchist Studies (IAS), aims to convert words into politically useful tools—for those already engaged in a politics from below as well as the newly approaching—by offering definitional understandings of commonly used keywords. Each Lexicon is a two-color pamphlet featuring one keyword or phrase, defined in about 2,000 words of text, and all pamphlets are available for free from the IAS, or can be downloaded here for printing and sharing. The first five pamphlets, designed by Josh MacPhee of Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative and printed by P&L Printing in Denver, are: “Power” by Todd May, “Colonialism” by Maia Ramnath, “Gender” by Jamie Heckert. “Anarchism” by Cindy Milstein, and “White Supremacy” by Joel Olson. Stay tuned for more titles in this growing series.

The Lexicon pamphlet series, a new project of the Institute for Anarchist Studies (IAS), aims to convert words into politically useful tools—for those already engaged in a politics from below as well as the newly approaching—by offering definitional understandings of commonly used keywords. Each Lexicon is a two-color pamphlet featuring one keyword or phrase, defined in about 2,000 words of text, and all pamphlets are available for free from the IAS, or can be downloaded here for printing and sharing. The first five pamphlets, designed by Josh MacPhee of Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative and printed by P&L Printing in Denver, are: “Power” by Todd May, “Colonialism” by Maia Ramnath, “Gender” by Jamie Heckert. “Anarchism” by Cindy Milstein, and “White Supremacy” by Joel Olson. Stay tuned for more titles in this growing series.

Gender

Gender is a system of categorizing

ourselves and each other (including bodies, desires, and behaviors) running through every aspect of culture and society,

and intertwining with other

categories and hierarchies (race, class, sexuality, age, ability, and so much

more). Various aspects of biology (for example, genitals, chromosomes, and body

shape) are interpreted to mean that human beings naturally belong in one of two

categories: male and female. But if we look more closely, we might question the

nature of gender. Biology, human and otherwise, is wonderfully diverse.

Nature

doesn’t give us these two options. We interpret and categorize, and then come

to believe that those interpretations, those categories, are the truth. Gender

doesn’t just happen. People define it, invent it. Even genital surgery on

intersex bodies is described as corrective, as though nature had made a mistake by not conforming to our binary

thinking.

Because

we invent gender, we can do it differently. This becomes clear when we look at

the many ways that throughout history and across cultures, different aspects of

social life and personality have been part of defining gender. What counts as a

“real” man or a “good” woman, as masculine or feminine, varies from place to

place and time to time. In some (sub)cultures, gender hasn’t been limited to

two options but instead includes recognition of three, four, or many genders.

The

usual story in countries like the United States, Canada, and the United

Kingdom, however, is that there are only two options. And while these states

may offer formal, legal equality, in practice they still largely value those

characteristics associated with men and masculinity (for instance,

independence, control, and strength) over those associated with women and

femininity (say, interdependence, love, and gentleness). This hierarchy can be

subtle or blatant, woven together with other hierarchies through institutions

and systems, socialization and culture, in ways that produce many complex effects.

In dominant cultures, mind and reason are imagined as both separate from and

superior to body and emotion; so too

is whiteness privileged over color, action over rest, hetero over homo, and

firmness over tenderness.

Gender

can be more or less rigid. Supposedly abnormal, unnatural, or improper gender

behavior can be met with social censure ranging from teasing to bullying,

discrimination, imprisonment, forced medical “treatment,” sexual violence,

emotional abuse, and even murder. This violence is most obvious when it comes

to transgender people, or those who otherwise transgress the social assumption

of two fixed and natural genders. Why does gender transgression trigger such

strong emotions, even to the point of violence? Perhaps it is because none of

us are perfect examples of a real man or real woman. No one can live up to

these abstract ideals, with all the contradictory messages about what they even

mean.

Most

people twist themselves into knots trying to conform to what they think they

should be, rather than simply being aware of who they actually are.

Self-policing one’s gender can feel so familiar, so habitual and subtle, that

the effort put into conforming may seem natural and effortless. Yet there is

something profoundly liberating in growing self-aware of the habits we hold on

to out of fear or shame, and when it feels right, learning to let them go.

Gender

isn’t just an individual experience, though. It’s intertwined with all of our

relationships and social institutions—many of which presently, if sometimes

inadvertently, serve to constrain, hurt, or control most people. Perhaps the

most obvious structure that does this today is the family, where people

generally first learn to notice the anxieties and expectations that come with

gender. Even the very idea of what a family is and how it works (or what it should be and how it should

work) is inextricably

linked with gender.

The

idealized nuclear family, for example, is defined as consisting of a

monogamous, married, and reproductive heterosexual couple led by the male “head

of household.” If the woman works outside the home, as is often economically

necessary at this stage of capitalism, she is still likely to do far more of the

housekeeping, emotional labor, and child care—with little or no recognition of

such tasks as work. Children are given gender labels from birth and may be

expected to conform to them. And while being the head of household has its

privileges, masculinity is frequently tied to one’s ability or not to provide

financially for the family, which in turn leads to a great deal of anxiety,

frustration, and shame in class-based societies.

The

wider political economy is also gendered in oppressive and exploitative ways.

Just as women’s labor inside the home is typically taken for granted, all sorts

of feminized labor is taken for granted in capitalism too. When people talk

about “the economy,” they usually are referring to a narrow and official

definition that only includes paid work, the production of materials or

knowledge, and the sales and distribution of those products. The economy, in

this understanding, doesn’t include the bearing and (unpaid) caring of children

nor the (unpaid) housework on which any economy depends.

Nor

does capitalism and related colonialist projects truly recognize the

traditional knowledge of noncapitalist cultures, whose extensive histories of,

say, working with plants are exploited by pharmaceutical and agricultural

corporations. Feminists of color have long noted the linkages between

colonialism’s unacknowledged dependence on the skills, wisdom, and labor of

people of color and women of all races. Many celebrated historical figures in

colonial nations are both white and male. There is nothing wrong with white men

per se, but neither is there anything as special about them as cultures of

white supremacy and gender hierarchy would encourage us to believe. Besides, no

one does anything on their own. We all depend on the efforts of others. While understated

in capitalist thought, such efforts have inherent worth and point the way to alternative economies.

Indeed, when work associated with women and femininity (such as

teaching, nursing, cleaning, and listening) is paid, it’s paid much less than

work associated with men and masculinity (such as sports, finance, leadership,

and talking). This gender hierarchy is further tied up with race and class inequalities when, for

example, higher-status women move into work traditionally associated with men,

thereby leaving feminized labor to lower-status women.

The

nation-state, too, is gendered. Like the traditional head of household, the

head of state offers protection in exchange for obedience. Its other characteristics

(including rigid borders, competitiveness, aggression, and independence) are

also those linked to certain versions of men and masculinity. Some nations

invade others in order to demonstrate their dominance, which once again

involves hierarchies of race and wealth. Like individuals or households

competing for economic success, nation-states are inherently insecure. By

simultaneously creating fear and promising security, they endlessly justify

their existence.

The

ways we categorize humanity into races, ethnicities, classes, and countries are

all gendered. Consider common stereotypes: the passive East Asian woman, the

hypersexual black man, the exotic other from across the border (whether of

nations or neighborhoods). Colonial invasions have long been justified by white

men (and women) drawn to both wealth and playing the hero, allegedly protecting

brown women from brown men. Ongoing inequalities are reinforced by continuing

to cast brown women and men, especially those in the so-called developing

world, in the role of a victim in need of charity.

Gender

divisions are rife with contradictions. Class hierarchies, for instance, can be

based on a division between manual labor (using the body, which is associated

with femininity) and so-called skilled labor (using the mind, and linked to

authority and control, which are all associated with masculinity).

Working-class masculine frustration often merely reverses this hierarchy,

suggesting that the strength of using one’s body is a more authentic form of

masculinity, while upper-class men with their clean clothes and soft skin are

effeminate.

Holding on to such resentment, to fantasies of superiority and a fear

of different cultures, is itself part of a gendered culture uncomfortable with

emotion. Instead of simply allowing emotions to exist and pass through us, or

finding other healthy ways to deal with our feelings, most of us are taught to

either cling to or reject them (which is really just another way of holding

on). Learning to be comfortable with our desires as well as our fears is part

of creating a world where we can live with and love ourselves along with each

other in all our differences and similarities.

Even our relationship with the rest

of the natural world (“Mother Nature”) is connected to gender. Inciting fear

and shame in people, about

either their own gender or gendered others (such as queers or foreigners),

induces a self-centered state of mind. When individuals feel threatened, they

of course prepare to defend themselves. They may do this by supporting war,

which has a profound ecological impact, or even through shopping. Making people

insecure about their bodies, and then offering products and services to address

the supposed imperfections, is fuel to the fire of a growth economy,

unsustainable on a finite planet. Self-centeredness (associated, for example,

with certain success-oriented versions of masculinity) can also lead to seeing

the bodies of other people, other species, and the earth itself as merely

“resources” available for one’s own benefit rather than beings in their own

right.

Gender

is a living, evolving system. It has no fixed truth. It changes as we change

our relationships with ourselves, each other, and the world. Gender diversity

is about the incredible beauty of life’s capacity to overflow, undermine,

subvert, and refuse all the categories we put on it, ourselves, and each other.

Compassion

can motivate people to seek

each other out, to support and nourish each other, to do gender differently.

Men who want to let themselves be gentle become friends. Women who know they

can be strong organize together and share skills. Drag queens and kings, bi

people and transfolk, lesbian women and gay men, and queers of all sexualities

make spaces for themselves and each other to connect, share, and play.

Friendships, networks, and movements can also include, cross, or transcend all

these identities and more.

Sometimes

people cling to gender identities to feel safe. At other times, they might hold

them lightly. Different spaces, different practices, can help people feel safe

enough to drop some of their own borders and self-policing in order to

experience gender lightly, playfully.

Families

can, of course, also embody alternatives to normative gender. Single mothers or

fathers, joint mothers or joint fathers, and

transgender parents all show that children do not need two parents of

supposedly opposite genders. Gender diversity in children can be respected and

honored. People can become conscious of how work is divided within the home.

We

can be less fixed and more experimental with our roles as well as identities.

Sometimes people create their own families, defined less by blood kinship and

more by affinity, friendship, and intimacy. People in social groups, movements,

and even neighborhoods can become family, developing their own rituals and

relationships. Housing cooperatives, queer networks of friends and lovers, or

extended families of other sorts all highlight that the heavily gendered ideal

of the nuclear family is only one possibility among many.

Economics

and politics can be done differently, too. The dominant systems of capitalism

and the nation-state are not the only options. They do not even represent the

majority of ways that people engage in economics or politics but instead simply

demand the most attention. Feminist geographers and economists, for example,

highlight the diverse economies that exist around the world—all the various

forms of producing, consuming, sharing, and working—that don’t fit into the narrow

(and macho) definition of the economy. We can acknowledge, celebrate, and

develop diverse, cooperative, caring economies, emphasizing their viability as

real alternatives.

Indigenous

activist-scholars and anarchist anthropologists note that many cultures, and

even some nations, do not have the same impulse to define clear borders or

police their own people— forms of social control that are taken for granted as

politics. Let’s notice in our own lives the difference between the official stories of who is in

control and how life actually

works. How might we

nurture the elements of our society that work cooperatively with other people

as well as ecosystems to create freedom, equality, and abundance?

Like

power, gender is everywhere, running through our relationships with ourselves,

each other, and the earth, and the relations between nations, classes, and

cultures. And like power, it is not a problem in itself but instead a question

of how we do it. Gender can be a pattern of control, violence, and domination.

Or it can be just another way of talking about the beautiful diversity of human

existence.

Lexicon

Series created by the Institute for Anarchist Studies/Anarchiststudies.org

“Gender”

by Jamie Heckert

Series

design by Josh MacPhee/Justseeds.org

Printed

by

February

2012

No comments:

Post a Comment